Literary Modernity

Tainan in Step with the World

A Move Toward Cultural Enlightenment

By the “roaring” 1920s, armed local resistance to Japanese rule had largely ended. Intellectuals seeking an outlet for continued dissent turned to the “New Society” movement. Literature was undergoing a transformation, as classical Chinese literary styles proved increasingly inadequate for the times. Chinese scripts, styles and creative media all became subjects of lively, sometimes heated, debate, and Taiwan intellectuals in search of change quickly found themselves charting exciting, contentious new territory. This was the advent of the New Literature (Shin Bungaku) Movement.

Even before the Taiwan Culture Association (Taiwan Bunka Kyōkai) was founded on October 17th, 1920, there were a number of grassroots political and social groups on Taiwan critical of unfair Japanese colonial policies. Newspapers and journals published by these groups from the 1920s into the early 1940s included Taiwan Seinen (Taiwan Youth) first published in Tokyo in 1920 and the Taiwan Shinminpo (Taiwan New People’s Post), which continued to publish until 1941. These publications provided an important forum for the writings of contemporary Taiwan intellectuals and represent an important and engaging archive of Taiwanese literary output during the Japanese Colonial Period. Article authors include some of Taiwan’s leading social and economic thinkers of the time. “By a Pond in Tainan Park”, published in Japanese in 1922 by Chen Feng-yuan in Vol. 3, Issue 8 of Taiwan, is considered a cornerstone work of the New Literature movement.

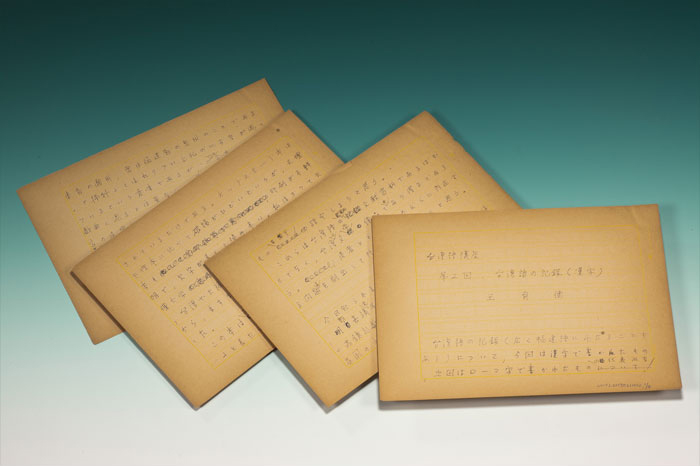

Despite the linguistic “about face” triggered by the end of the Pacific War in August 1945, Taiwan’s authors continued writing and commenting on the changes engulfing their island. The end of Japan’s colonial rule and the arrival of the Nationalist Chinese army, ROC government and countless refugees from war and revolution changed forever the intellectual landscape both of Tainan and of Taiwan. While most intellectuals of the period had been born in the 1920s and experienced the terrible years of the Pacific War, some had spent their entire life in Tainan, while others had found their way to Tainan with the newly reconstituted ROC government. Both groups were to make important, indelible contributions to Tainan’s intellectual and literary fabric. There was also a third group that, while born and raised in Tainan, had left and now lived elsewhere. Whatever worldly experience they gained, the work of these emigrants would be forever enriched and nourished by memories of Tainan's cityscape of red brick homes and stolid city gates.

Literature Set to Music

The rich beauty of life found its expression in song throughout the colonial period. Dedicated to preserving and promoting local cultural mores, the Taiwan Culture Association, apart from its regular island-wide lecture series, also gave a “voice” to Taiwan in music, film, and live theater performances. Young Tainan songwriters including Huang Chin-huo, Chao Li-ma (Chao Chi-ming) and Tsai Teh-yin successfully promoted their work through major contemporary record labels such as Columbia, Popular and Taihei. The husband and wife team of Lu Ping-ting and Lin Shih-hao created treasured songs by Taiwanese for Taiwanese. Lu’s creative talent generated such memorable songs as “The Weaving Maiden”, “Boat in the Moonlight”, and “Behind the Screen Window” that Lin’s sonorous voice made famous.

Voices for the Vernacular

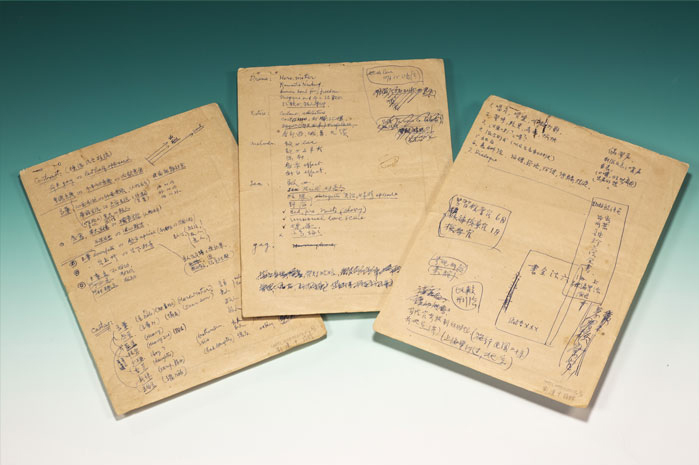

Chen Tuan-ming’s article entitled “Writing the Way We Speak” published in 1922 in Vol. 4, Issue 1 of Taiwan Seinen was the first article published in Taiwan to advocate the use of vernacular, rather than classical, Chinese in print. Originally scheduled for publication in the banned December 15th, 1921 issue (Vol. 3, Issue 6), it was included in the next issue published 36 days later. In October 1923, the Taiwan Culture Association made the decision to back so-called “Church Romanization” (aka Pe̍h-oē-jī) method promoted by Tsai Pei-huo as a system to write vernacular Taiwanese. Books written using the new system began to circulate. Tsai established the Taiwan Vernacular Society in 1929, which proceeded to hold a series of three Pe̍h-oē-jī workshops at Tainan’s Wu (Martial God) Temple that promoted this “simple to learn, easy to understand” writing system.

The Taiwan Church News (Tâi-ôan Hú-siâⁿ Kàu-hōe-pò), in print since 1885, was co-opted as a platform for the New Literature Movement, publishing many original works, revised works, and translations including Cheng Hsi-pan’s “Line Between Life and Death” and Lai Jen-sheng’s “Enemy Adorable”. The plethora of new vernacular works highlighted the vernacular movement’s vibrant underpinnings.

Art For the Masses; Literature Speaks Out

Society has fallen to such depths because of you … you rice-eating maggots! He cursed what society had become. Some enjoy food, nice clothes, a place to live and the luxury to spend their days in the pursuit of pleasure. Others are destitute. Without even half a bowl of gruel to warm their bellies, they live a harsh existence and die early deaths … (Chu Feng; The Unemployed)

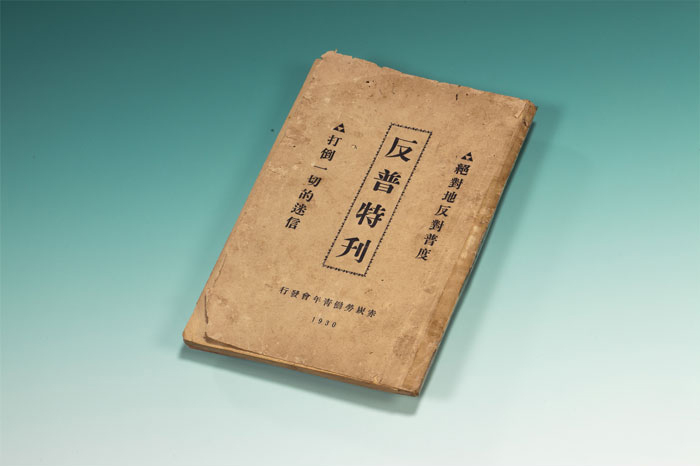

The Taiwan Culture Association held educational activities island-wide. Tainan Seinen was at the fore of most core movement issues, including improving general public habits. Those with left-wing socialist views joined to found Equator Press, which published the newspapers The Equator and The Flood as well as the journal Deconstructing Superstition.

The movement expressed itself most brilliantly in its original play scripts. In March 1927, a troupe of youths from Tainan and Anping gave public performances of Love’s Triumph, The Freedom of the Unfree, Life’s Fragile Bloom, and The Great Nincompoop at the Minamiza Theater in what was then the center of Tainan City. Performances included musical interludes and solo performances. Lu Ping-ting and Chuang Sung-lin were two of the period’s most celebrated artists, with Lu performing on stage and Chuang writing acclaimed new scripts. New Literature-inspired plays poked fun at tradition and social conservatism while extolling sexual freedoms and social equality. Scriptwriters put pen to paper to expose the true nature of both capitalism and imperialism. Tainan native Yang Kui, one of the movement’s leading lights, won a coveted 2nd place recognition (the 1st place prize went un-awarded that year) from the influential Japanese literary journal Bungaku Hyōron (Literary Review) for his novel Shimbun Haitatsu Fu (The Newspaper Boy). Although Yang Kui was the first Taiwanese author accepted by Japan’s literary community, colonial authorities banned his award-winning work in Taiwan. In other works such as The Doctor-less Village and Mother Goose Gets Married, Yang turns an embarrassing spotlight on the inequities of the capitalist class system.

Literary Societies

As we inaugurate this branch, we embark on something much greater than simply expanding and strengthening the TLAWU. We are expanding and advancing our innate nativist consciousness. Having been so bold as to plant the tenuous flower of literature in these salty soils of ours, we have every confidence it will bear succulent fruit. (Proclamation at the Founding of the Chiali Branch of the Taiwan Literature and Art Workers Union)

Taiwanese authors, of both the classical and new schools, enjoyed the company of like-minded intellectuals. They gravitated naturally into literary organizations, which published and distributed works by their members and helped turn ideals into action. Classical poetry societies had been popular with Tainan’s intellectual elite since the earliest days of settlement. On the heels of the New Culture Movement, Tsai Pei-huo founded the Taiwan Vernacular Society in 1923; Huang Hsin created the Culture Troupe, which later reorganized as the Tainan Assistance Society; and Wang Shou-lu and Han Shih-chuan founded the Tainan Cultural Theater Troupe in 1926. Yang Chih-chang and Lin Hsiu-erh of the well-organized New Literature Society founded Le Moulin (the “Windmill” Poetry Circle) in 1933 to advocate avant-garde thought and create surrealist works. In 1930, the Southern Taiwan Society joined with the “Spring Oriole” Poetry Circle to found 3-6-9 Publishing House, which grew into a leading voice for popular literature. In 1935, Wu Hsin-jung, Kuo Shui-tan and Wang Teng-shan founded the Chiali Branch of the Taiwan Literature and Art Workers Union and, in 1936, Chao Li-ma and Chuang Sung-lin founded the Tainan Art Club. The Tainan Branch of Taiwan Shin Bungaku (Taiwan New Literature) opened in 1936 as well. These important organizations, all based in Tainan, were instrumental in setting the tone and meaning of contemporary culture reflected in Taiwan literature.

The decades following Taiwan’s handover to the Republic of China in 1945 was a period in Taiwan literature clouded by doubt and uncertainty. Growing demands for freedom and democracy found a voice again in literature in the years and decades following the 1979 Kaohsiung (Formosa) Incident. It inspired Huang Ching-lian, Tu Wen-ching, Lin Fo-erh, and Yang Tze-chiao to organize the Salt Flats Literary Camp in that same year. Elder statesmen of the New Literature movement including Lin Ching-wen, Lin Fang-nien, Hsu Ching-chi and Kuo Shui-tan attended the camp’s first gathering at Tainan’s Nankunshen Temple. They breathed life into the growing movement for literature and literary expression in postwar Taiwan. The Salt Flats Literary Camp shaped debate about and the development of Taiwanese language (Hokkien) literature and local language renaissance and opened the door for writings on critical social topics such as the 1947 February 28th (228) Incident. The torch had been passed to a new generation, and the Salt Flats Literary Camp was now at the vanguard of literary realism in Taiwan.

The new literary spirit soon spawned the birth of complementary activities such as the Hai Ong Hokkien Literary Camp and the Jung Hou Hokkien Poet Awards, which, while rooted in Tainan, expanded nationwide and indelibly influenced the modern course of Taiwan literary history.